With her vibrant artwork, full of shape, colour and texture, Annie Crawford is making a statement. And it has extra power because, as someone with autism and selective mutism, she’s hasn’t spoken a word since she joined UCA two years ago.

Annie studies BA (Hons) Fine Art at UCA Farnham, and her work reflects her life experience. We asked Annie over e-mail to talk about her practice, her time at UCA and how her autism and selective mutism both affects and inspires her.

Hi Annie, thanks so much for chatting with us. Can you tell us about your degree so far — how has it helped you develop your style and identity?

I’m really enjoying my degree so far. My art practice has developed so much. Before I started, I’d never done anything sculptural or abstract. I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything differently now. My course has really helped me to understand the way I truly like to work. I feel much more passionate and connected to what I produce. The degree is definitely more challenging than I expected — but in a good way.

So, what are your art inspirations?

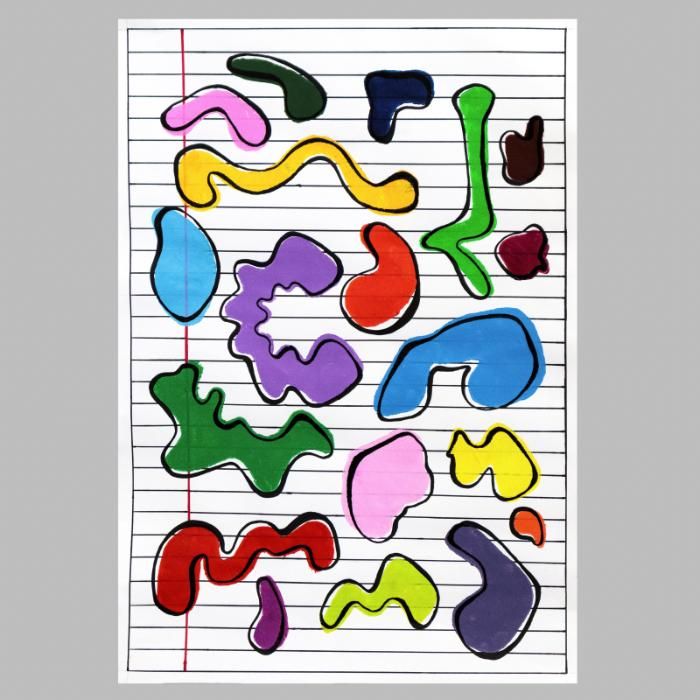

My art practice is about ‘Pre-speech’ — the internal formation of letters and words before they become external speech. I’ve developed a series of abstract shapes that represent words in their unformed state.

I’m particularly interested in neuroscience and the study of linguistics. I think my own difficulties with the use and understanding of language have led me in this direction. Quite often I feel as though I’m forming words, but I can’t verbally express them, so in some ways, my work reflects that experience. I make something intangible (the formation of Pre-Speech) into a tangible representation. I’m also very inspired by colour and the energy it can bring to my work, but also the effect it has on people — like colour psychology.

In terms of artists, I’m very inspired by Franz West, Dan Lam and Paul Cox’s “sculptures alphabétiques”.

You’re very open about your autism on your Instagram page — can you tell us more about how it affects you personally, and does it influence the way you approach your work?

Autism is a lifelong developmental disability that affects how people communicate and interact with the world. It’s a spectrum condition and affects people in different ways. I have problems with social communication and interaction. That means difficulties with interpreting both verbal and non-verbal language, taking things literally and needing extra time to process information or answer questions. I also often have difficulty ‘reading’ other people — recognising or understanding others’ intentions — and expressing my own emotions. This makes it hard to form friendships and I get easily overloaded.

I find the world a very confusing place and I prefer to have routines so I know what’s going to happen. A change in routine can be very distressing.

I also have sensory processing disorder, which means I may experience over- or under-sensitivity to sounds, touch, tastes, smells, light, colours, temperatures, or pain. There are lots of places I avoid going because of these sensitivities. For me, too much sensory input leads to sensory overload and shutdowns. Unfortunately, this happens quite a lot when I’m on campus, but I’ve learned ways to manage it — such as wearing noise-cancelling headphones when it gets too loud. Sensory overload is very exhausting.

Being autistic also means I have highly focused interests in specific subjects and have become very knowledgeable about them — for me it’s linguistics and art. I can retain a lot of information about these subjects, but it can be very difficult to remember other things. This is because I have poor executive function — I have trouble organizing my thoughts, accessing, and integrating the information to make it useful.

Autism definitely affects the way I approach my work. Having such a focused interest in my chosen subject has been very beneficial, and once I start a piece of work, I remain very absorbed in it — sometimes forgetting other tasks. However, there are other times when I struggle to get started, even though I’ve planned exactly what needs to be done. This means I have periods of doing a huge amount of work — burning myself out, and then having a period of not being able to do anything. It can be frustrating, but this is the way I function and, so far, I’ve been doing very well with my degree despite it. I’d also say that both my disabilities have an impact on the content of my work.

And on a similar note, how does your selective mutism affect you — what should people know about it and how can they support others?

Selective Mutism (SM) is an extreme anxiety disorder in which a person who is usually capable of speech cannot speak in specific situations, with specific people or in specific places. A lot of people think it’s a choice, but in actual fact, anxiety levels are so high that is causes vocal cord paralysis. I was diagnosed with ‘severe’ Selective Mutism, which means I’m only able to speak around my close family. I’ve never spoken at university. There’s no link between Selective Mutism and Autism, but it’s likely I developed SM as a way to mask the difficulties I have with social interaction.

As I’m unable to verbally communicate at Uni, I’ve had to advocate for myself a lot, to make sure things could be adapted. It’s been challenging at times, but for the most part, my peers and tutors are very accepting. Selective Mutism can affect all types of communication; there are days when I can only respond to people with gestures, like nodding or shaking my head. But when I can, I write or type things if I want to share my thoughts. There’s never any pressure, which is really important.

There are a few key things to remember when supporting someone with this condition.

- First of all, try to create a comfortable environment and remove all pressure to speak.

- Asking yes/no questions can be helpful — that way they can easily respond non-verbally.

- Accept any form of communication.

- When they are able to speak, it’s important not to make a big deal out of it. Try to act normal. Otherwise, they could start to feel uncomfortable and they won’t be able to speak to you again.

- Be patient. It’s a good idea to give them a few seconds to respond.

- And lastly, educate yourself! This way you’ll understand what they’re going through.

So how did you feel joining UCA — what made you choose us?

When I visited UCA on an open day I felt very comfortable, and I knew it was the right choice for me. The tutors were very nice, and the learning support team were very reassuring, they clearly explained how they’d be able to support me. But naturally, I was quite anxious about starting university, particularly because I didn’t know how people would react to my difficulties and the fact that I’m unable to communicate verbally. Selective Mutism isn’t a very well-known condition, so I always knew it would be challenging to get people to understand, whichever uni I picked. I’m so glad I chose UCA; I’ve met an incredible group of people on my course and everybody looks out for each other.

What support has UCA offered you, and how has it helped?

Ever since I started at UCA, I’ve had assistance from the learning support team. I have a support plan in place and work with a learning support assistant. They’ve also helped me to get DSA (Disabled Student Allowance). Through DSA I’ve been able to get specialist one-to-one mentoring, specialist one-to-one study skills support, specialist equipment and software for recording lectures and making notes. It means I can access my course more effectively.

I quickly become overwhelmed when I’m on campus, by the course content and sensory input. It leaves me feeling exhausted most days, so having my mentor to discuss these types of things with has been incredibly helpful. Any issues I have, we can work out how to manage them. The support she’s given me has helped me step out of my comfort zone and try things I thought I couldn’t do, like participating more with group projects.

I’m very grateful for all of the people I have supporting me at UCA — without them, I’d be struggling to manage the demands of my course.

What advice would you give to people who might be considering a degree at UCA and may have a condition or disability that means they need some extra support?

I’d encourage them to declare their disability and apply for DSA before they start the course so that the support they need is in place from day one. Let your tutors know, too — I emailed mine before starting the course and sent a copy of my support plan. UCA has a very supportive community, there are plenty of people who can help with any issues. I’m also lucky enough to have peers who are happy to speak up for me if something’s not right. Joining the freshers’ group on Facebook and getting to know some of the people on your course before the first day is also very helpful.

Finally, what are your career aspirations after you graduate?

I’m still considering what I want to do after I graduate. I’m considering doing an MA in fine art at UCA to expand my knowledge and contacts or starting to develop my work as a freelance artist. I think the decision will be clearer to me in my final year, but I’d definitely like to get my work out into the public domain and use it to create more awareness of Selective Mutism and Autism.

You can find out more about Autism on the National Autistic Society website, and read more about Selective Mutism on the SMiRA site. Or visit our website if you’d like to know more about UCA’s learning support services.

/prod01/channel_8/media/marketing-media/Annieheader-small.jpg)